When Andrea Lazzarotto publicly released Fuji (Forensic Unattended Juicy Imaging), I was actively maturing internal corporate processes to respond to security incidents involving macOS machines. Having experimented with Fuji, it became part of our overall data collection strategy as it is repeatable, accessible and efficient. As of May 2025, Fuji offers three acquisition capabilities named after their respective macOS utilities: ASR, Rsync, and Sysdiagnose.

True to Lazzarotto’s goal, Fuji has a user-friendly interface that allows the examiner to logically acquire the entire drive or a single folder that is open source. A short video by Richard Davis of 13Cubed is likely all you need or want to get started with Fuji.

For additional insight about Fuji’s development and Lazzarotto’s work, his interview with Forensic Focus and SANS presentation are enlightening. In Lazzarotto’s interview with Forensic Focus, his response on why open-source software is important should be on the minds of all examiners:

The most important aspect, I believe, is the ability to understand what a tool does and the chance to ensure the process is repeatable.

Rather than summarize how to use Fuji, I’m taking on that quote as a call to action; this post explores how Fuji uses native macOS utilities to logically preserve data on Mac machines.

Background

Despite administrator access to a fleet of corporate Macs, they are generally more hardened and requires a different process to collect data from compared to a machine running Windows. With the newest generation of Macs, acquiring a physical image, and decrypting it, hasn’t been possible; for several years at least. For modern Silicon Macs, we must rely on native capabilities to logically preserve data that exists on a synthesized container disk.

In SANS FOR518, and Sumuri’s MFSC-101 and MFSC-201, a handful of methods were discussed to acquire data logically. FOR518 touched on using Apple System Restore (asr) and Sumuri reviewed the use of rsync.

sudo asr restore --source /dev/disk3s5 --target /dev/disk4 --debug --erase --verbose

OR

rsync -avE /directory-to-copy/ /Volumes/[destination]Using either requires a destination using an Apple native image format to preserve Apple Extended Attributes like an Apple Disk Image (.dmg) with extra space:

hdiutil create -fs apfs -size 500GB apple_evidence.dmg

THEN

sudo hdiutil attach -nomount apple_evidence.dmgSANS FOR518 and Sumuri present methods in their respective courses to collect Unified Logs from macOS devices.

log collect

OR

log show > /Volumes/[destination]FOR518 additionally covers the command sysdiagnose, a LOOBin (Living Off the Orchard Binary), to collect other pattern of life data, which includes Unified Logs as part of that data dump.

sudo sysdiagnoseIf a response or collection process is well-defined and practiced, these commands are relatively straight-forward. With a tool like Fuji, however, I am less likely to make a mistake i.e., miss-type a command, create a .dmg file with the wrong filesystem or make it too small for the collection.

Logical Acquisitions with Fuji

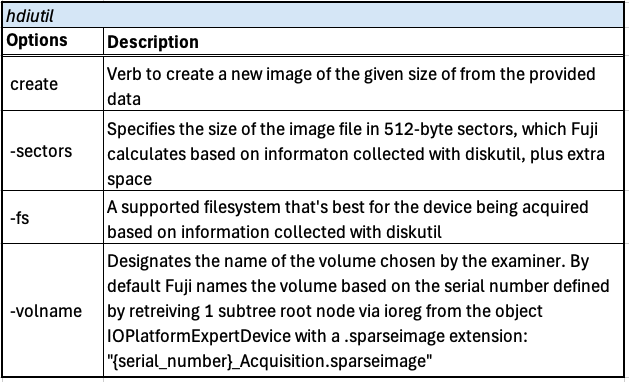

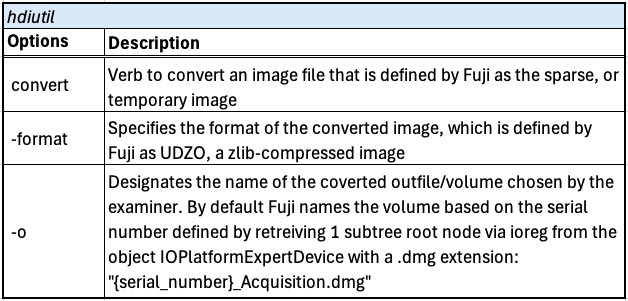

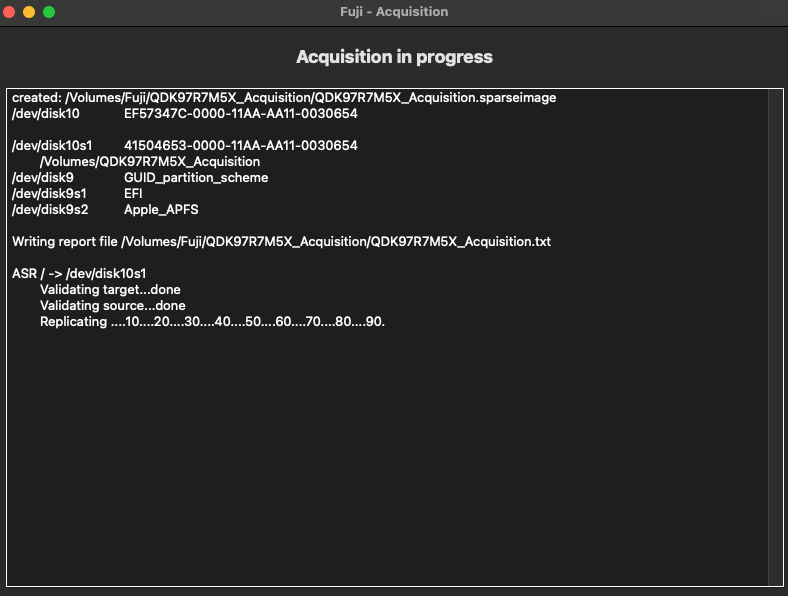

In Fuji, Fuji.py contains the code related to the graphical user interface. Abstract.py, in summary, prepares the acquisition process for all methods Fuji is capable of. It defines the parameters to create a temporary image (sparse image), convert it to an Apple Disk Image (.dmg), keep the system from sleeping during acquisition, and saves pertinent information about the macOS machine in an acquisition report.

Fuji Acquisition Method: ASR

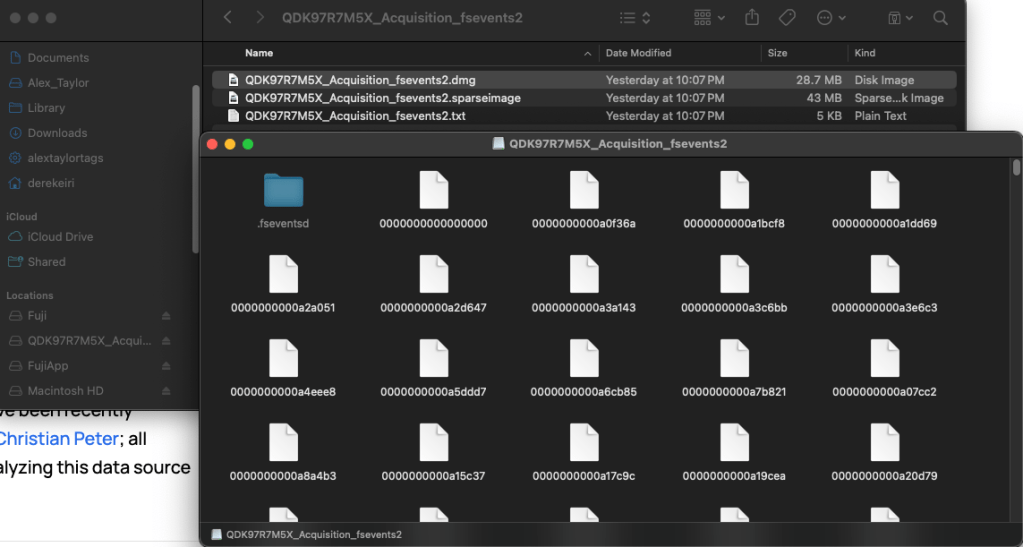

Intended for restoring and cloning macOS systems, asr may be repurposed for preserving data from volumes in a forensically-sound manner. The caveat, however, is that asr does not capture .fsevents of the target Mac, which records “historical file system activity over time“. The .fsevents directory may be copied out or collected with the rsync command to preserve as much metadata as possible.

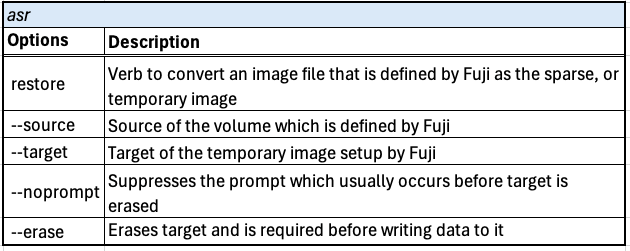

In Fuji, asr.py establishes the parameters to prepare an Apple Software Restore including the acquisition report. It then issues the asr command to restore the root volume and saves it to the temporary image set up by Fuji. When the temporary image is erased and data begins to save data to the target, the prompt to confirm to erase its contents is ignored.

Fuji Acquisition Method: Rsync

The rsync command was featured in Sumuri’s MFSC-101 and MFSC-201 class as a method to logically copy data from a live Mac and preserve Apple Extended Attributes. It may also be piped after the find command of certain files, then copy to a destination. Fuji explains that while rysnc is slower, it may be used on any source directory. The .fsevents directory is a perfect candidate for this method.

The rsync.py script prepares parameters to run the rsync command to only look within the partition, perform the task recursively, preserve as much metadata as possible, show progress of the transfer and exclude files with the goal of preventing duplicates of the same file.

Fuji Acquisition Method: Sysdiagnose

Volatile data sources like Apple Unified Logs have recently been discussed by Alexis Brignoni, Lionel Notari and Christian Peter; all highlighting the criticality of preserving and analyzing this data source from iOS devices.

FOR518 also touch on application usage, connected devices, and more by analyzing powerlogs generated after running the sysdiagnose command, which also collects Unified Logs. While analysis may be performed using the Console app, or with log show commands, a feature of Fuji is that it outputs the Unified Log into an SQLite database!

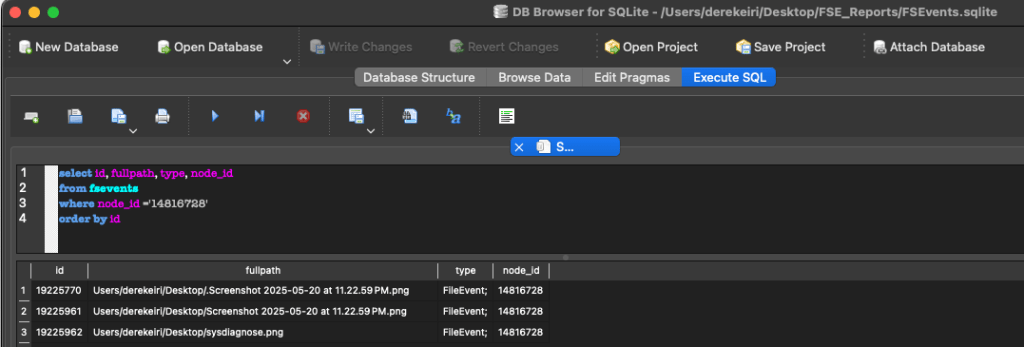

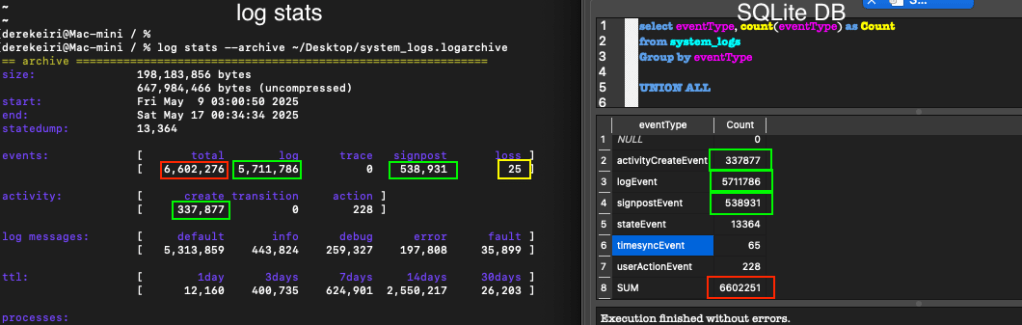

The Sysdiagnose.py script first creates the SQLite database and table structure, then issues the sysdiagnose command. The script then uses the log show command to display events, including levels not shown by default, from the system_log.logarchive file collected from the sysdiagnose output. The events are displayed in a newline delimited JSON format and streamed by row to the SQLite database, system_logs.db.

Running this option will take some time to complete.

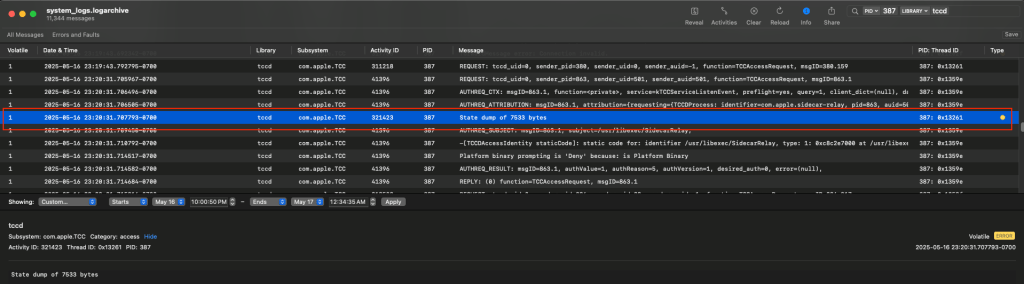

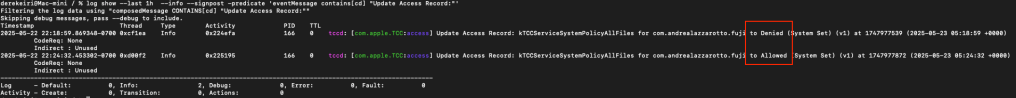

The Console app is an option to preview the log, but it appears some events are not viewable. For example, I noted a “State dump” occurred involving the Apple Trust Consent and Control (TCC) subsystem.

To review the log at a granular level, and the contents of the state dump, it may necessary to review the log using the log show command.

With Fuji creating an SQLite database and populating it with data the system_log.logarchive it collected, I believe this approach makes the information more accessible to search and run queries from.

Fuji handles each valid event quite well. Though the total counts from each method are different, it seems the “loss” events contribute to the total events counted with the log stats command compared to the total queried against system_logs.db (FYI: Notari wrote about how the log stats command works, and incidentally, is used in his parsing tool, here).

For me, the flexibility between querying SQLite database and running the log stats command makes the data more accessible.

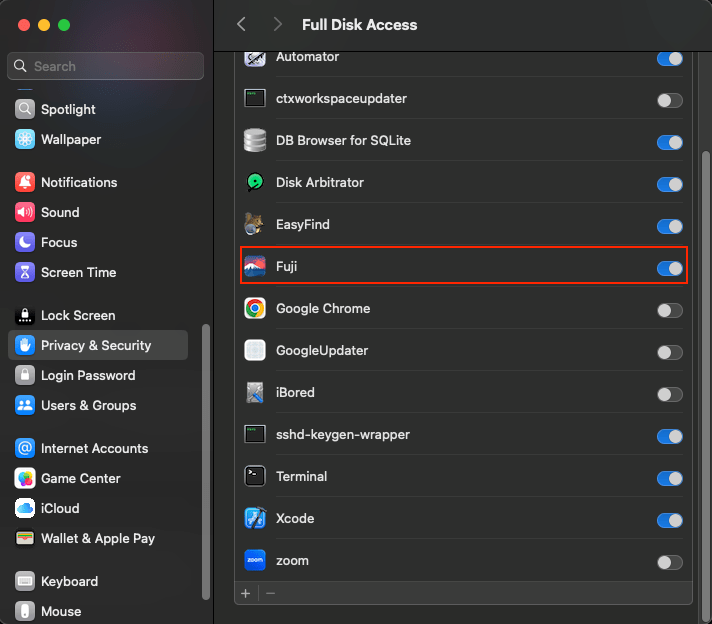

Tangent: Reviewing the state dump, I was reminded of Sarah Edwards’ research on tracking app permissions. Here, I’m just switching Fuji’s Full Disk Access permissions.

From Edwards’ research, the entries were “removed anywhere from about 1 hour to 1h40m.” It seems with state dumps of the TCC database recorded with Unified Logging, it may provide the status of an app’s permission as it was about 7 days earlier.

What’s Next?

Based on what is publicly available, I’m aware of the following updates to Fuji that may come next:

- File system acquisition using Fuji from the macOS recovery environment. This is similar to how NETRE acquires data except Fuji is free and will not be advertised as a “physical acquisition”.

- Save Fuji’s Sysdiagnose collection within a .zip file instead of a .dmg.

- Adding the option to create an uncompressed .dmg (UDRW), an image format X-Ways Forensics supports

Conclusion

Fuji is an acquisition tool that logically collects data from macOS machines with a simple graphical user interface. It is capable of three acquisition methods: Asr collects data from volumes, Rsync collects data from directories, and Sysdiagnose collects system data and Apple Unified Logs. Fuji also converts Apple Unified Logs to an SQLite database.

In agreement with Lazzarotto’s belief that it is important to understand what a tool does, I reviewed the python scripts in Fuji’s GitHub repository to better understand the native macOS commands behind the tool.

When I occasionally find a free tool so cool or important in my daily work, I’ll make a small financial contribution to the project. Fuji happens to be one of those projects.

A special thanks to Andrea Lazzarrotto for his time reviewing a draft of this post; he helped me ensure this post’s summarization of Fuji’s implementation of macOS native tools is an accurate representation of his code.

Resources

Here are links I found helpful writing this post to provide additional context or understanding, but not specifically cited.

https://github.com/ydkhatri/Presentations/blob/master/macOS%20Forensics-MUS2020.pdf

https://eclecticlight.co/2019/09/02/interested-in-performance-updated-signpost-tools-now-available/

https://github.com/cheeky4n6monkey/iOS_sysdiagnose_forensic_scripts

Feature image generated with WordPress’ Jetpack AI Assistant.

Leave a comment