Early Hurdles

During my early search for corporate digital forensic roles, one of the challenges I encountered was demonstrating experience. Despite having 12 years of experience with corporate investigations, nearly all of which involved handling and reviewing logs, interviewing, writing reports, and attributing behavior to an individual, it wasn’t digital forensics. I was surprised how little investigation experience appeared relevant for the roles I applied for. Even certificates and training in digital forensics seemed to have little weight (I know better now). I felt frustrated.

At the start of my career, I understood attribution is the primary driver in any investigation I conducted. The memorandum from former Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates, dated September 15, 2015, was a notable event in healthcare compliance:

“One of the most effective ways to combat corporate misconduct is by seeking accountability from the individuals who perpetrated the wrongdoing. Such accountability is important for several reasons: it deters future illegal activity, it incentivizes changes in corporate behavior, it ensures that the proper parties are held responsible for their actions, and it promotes the public’s confidence in our justice system.”

Yates’ memorandum provided guidelines to federal attorneys on holding individuals accountable involved in corporate wrongdoing. Of interest to corporate compliance officers, an organization may qualify for cooperation credit when an organization voluntarily discloses all facts and individuals relating to misconduct unknown to the government. Cooperation credit may benefit the organization in the form of reduced damages, and civil penalties, but only if investigations are prompt and thorough. The message was clear for healthcare compliance programs, and leadership, that there was an incentive to “get it right”. It’s not too different when supporting an investigation with digital forensics.

I used to think about what would have given me an edge in my effort to land my first role in digital forensics. What was I missing?

A Book on a Mindset

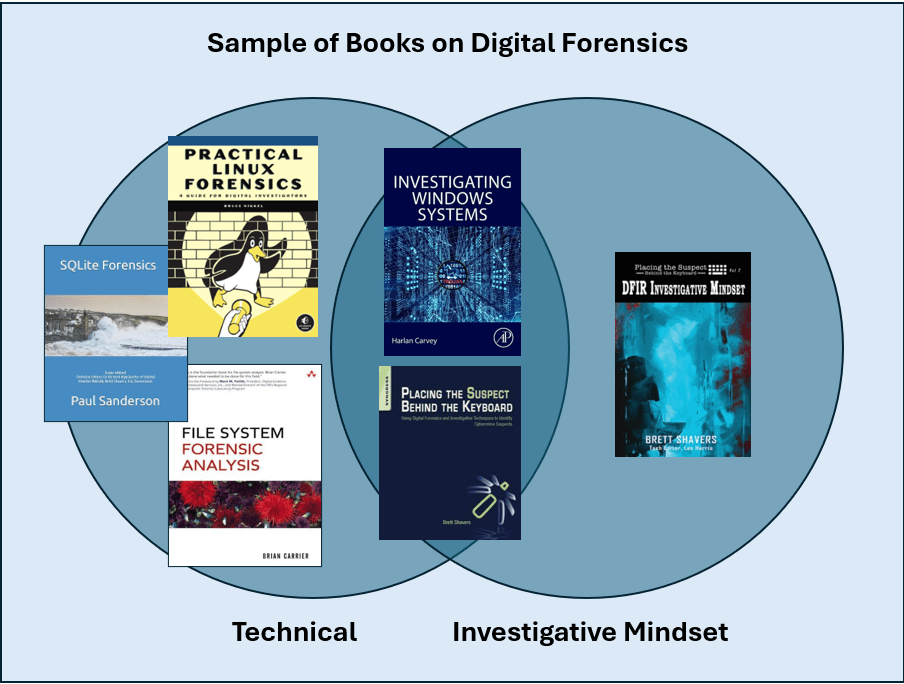

Early this year I read a beta copy of Brett Shavers’ newest book, Placing the Suspect Behind the Keyboard: DFIR Investigative Mindset. Reading Shavers’ book reassured me that Digital Forensics & Incident Response (DFIR) is more than just technical knowledge of computer systems. Shavers describes it as systematically using everything available to you to gather and process information objectively, and present the facts in a narrative to an audience; all while not permitting your technical ability to stagnate. Moreover, it’s about attribution.

Shavers’ first published book, Placing the Suspect Behind the Keyboard, hints at the DFIR investigative mindset by combining technical and investigative skills in a guide on how to conduct investigations involving electronic evidence. DFIR Investigative Mindset, however, explicitly focuses on developing, or advancing, investigative ability and living a “daily life of a critical thinker”.

My first exposure to the investigative mindset was a university course on technical writing and a community college course on police report writing. Both courses emphasized the importance of communicating effectively, and objectively, to a target audience with an explicit goal. As I progressed professionally, I received regular training in performing investigations and conducting interviews. It was foundational in growing my career. I was also fortunate to learn from the experience of seasoned investigators I had the privilege to work with.

Reading DFIR Investigative Mindset has helped me identify areas of improvement, enhance self-awareness, and validate characteristics I also believe to be important.

The Edge

While I’ve been fortunate to accumulate experiences, education, and training in the investigative mindset, a book like DFIR Investigative Mindset would have given me laser focus on my transition to DFIR. Today, it provides a guide to audit my progress.

Then

Based on my perspective when I was searching for my first digital forensics role, and hindsight, the following are a handful of nuggets from DFIR Investigative Mindset that would have been extremely helpful to me:

- Shavers encourages readers to engage in a self-assessment exercise in Chapter 3. This exercise would have helped me recognize that my technical skill had ample room to grow, despite investigative training and a couple of digital forensic certifications. Learning does not stop.

- Shavers’ chapter on Tactics, particularly on problem-solving, would have influenced me to consider how to map my existing “old-school” investigative skillset to solve high-tech problems sooner. While I primarily credit Placing the Suspect Behind the Keyboard as an early guide, DFIR Investigative Mindset is more direct.

- Likely the most impactful lesson to me would have been Shavers’ chapter on Strategies. On decision-making, I would have an early appreciation that each “forensic artifact […] fits somewhere on the reliability scale and, separately, somewhere on a credibility scale.” For example, not every artifact described as “Evidence of Execution” is equal in reliability or credibility, especially in isolation. There must be an understanding of that artifact in relation to other artifacts and data sources.

Perspective: I started my DFIR journey sometime in 2017; only through experience was I able to gain a smidge of these lessons around 2020. I suspect if I read this book (and it existed) in 2017, I estimate it would have advanced that by 12-18 months.

Now

Complacency, or other competing priorities (e.g., life), may cause atrophy of the attributes that embody a competent DFIR investigator. There is value in reviewing and re-reading DFIR Investigative Mindset to prevent this. As I continue to gain experience and wisdom, I can periodically reflect on my notes and find new inspiration in familiar words to keep myself honest.

At least until next time, the following are a few topics I especially find helpful to me now:

- I started to practice a fun exercise on creative thinking in Chapter 5; identify an object’s intended purpose, then think of alternative ways an object can be used. This exercise inspired more through systematic troubleshooting and frequent cycles of trial and error in my daily work.

- As much technical knowledge I’ve internalized, it can be a challenge to translate it to the appropriate audience. As I continue to grow in influence and decision making, Shavers’ advice on “thinking like a…” reminds me to be considerate of the target audience and fulfill my responsibility to comprehensively understand their needs. I must not rely on others to recognize or assume the value of my skillset; I have the responsibility of understanding their needs and how I can help. I must think like a(n) (employer | customer | client) to understand their perspective or teach tech to clients. Shavers may have mentioned in a presentation or recording that someone had an idea to write a book on analogies for DFIR. Maybe like a DFIR version of Big Ideas, Little Pictures? I’d buy that book.

- In Chapter 8, Shavers describes the states of competence and expands on it in a blog post here. To me, it’s a cautionary reminder that “skills can improve and degrade over time”. Shavers offers a solution; embrace a higher level of competence that is always reflecting and open to improvement: infinite competence. For every task I execute, I aim to exercise this level of competence.

What was missing?

If DFIR were easy, there’d be no need for DFIR.

If DFIR were impossible, there’d be no DFIR.

-Brett Shavers

As I was searching for my first digital forensics role, technical skill may not have been the only thing that was “missing”. Might it be possible that the employers hiring for the roles I applied for did not understand the difference between digital forensics and incident response or acknowledge the role of attribution? Maybe. But that’s irrelevant.

Other contributing factors may have included insufficient preparation in conveying how my previous experience was relevant to their needs, what digital forensics knowledge I knew at the time and how I would apply it, and what I was doing to improve my skillset. This is standard job interviewing stuff, and coincidentally, the competency of a DFIR investigator is always being evaluated. After understanding and applying those concepts, I eventually landed my first role in digital forensics. I am nearly certain DFIR Investigative Mindset would have enabled me to understand those concepts sooner.

I believe maturity in this field, or any discipline, is recognizing and learning from challenging experiences. Hurdles I’ve encountered, and overcame, are part of my growth.

Comparing my capability now and then, I had a lot to learn (still do) about applying investigative skills using digital information. I have every expectation that I will continue to encounter problems; it’s my responsibility to figure them out. Fortunately, I have Shavers’ experience and wisdom written in DFIR Investigative Mindset to guide me.

Edits:

2024-12-02: Grammar

Leave a reply to Week 49 – 2024 – This Week In 4n6 Cancel reply